John Oxley restoration

Update – December 2013

Sydney Heritage Fleet is a volunteer based non-profit organisation that continues its restoration of the last remaining coastal steamship in Australian waters.

John Oxley was built in Paisley, Scotland and steamed out to work in Australian waters for the next 40 years. Image – John Oxley on her trials trip just before steaming to Brisbane – 1927.

John Oxley was laid up when handed over but after some hard work by SHF members, was steamed from Brisbane to Sydney under her own power and with a crew of museum volunteers. The fledgling museum then was able to steam this remarkable survivor from the age of steam for trips on Sydney Harbour and even undertook a number of trips to nearby ports of Newcastle and Jervis Bay.

In 1973 John Oxley was laid up because of concerns over thin hull plates. It would be 27 years before Sydney Heritage Fleet would be able to commence serious restoration on this iconic steamship.

Over these years; however, the SHF workforce worked to restore other SHF vessels, all the time rediscovering and practising the skills needed to rebuild John Oxley.

In 1997 the tired old hull of John Oxley was placed onto the Sea Heritage Dock. It is a purpose built barge that was constructed so that SHF vessels could be restored out of the water at a slower and more cost realistic pace.

Restoration officially commenced in 2002 when a few volunteers cut into the main hold of John Oxley. The work has continued. 2012 saw the last hull plate in place and the rudder was returned in 2013. The second half of 2013 has seen work focus on removal of the last asbestos insulation from the main engine, work on replacing the badly corroded main deck steel plates and the commencement of work on rebuilding the bridge deck.

The restoration would not be possible without the support of our workforce, whose efforts and skills in so many areas are driving this restoration forwards.

Thanks are also extended to our anonymous sponsor and to our sponsors in industry who continue to support this project. This restoration is a long term project and we thank you for your continued support.

Recent changes to John Oxley’s appearance

Passers-by and visitors will not considerable changes to the appearance of John Oxley. There is no escaping the visible impact of recent work as funnel, wheelhouse and bridge deck have been removed for restoration.

We hope that the 17,000 or so commuters that travel on nearby Victoria Road realise we have substantially completed the less visible parts of the ship and are now working on very visible upperworks.

Asbestos removal – main engine cylinder insulation

Asbestos insulation was prevalent in the steam age. Boilers and steam pipes were just about universally lagged in asbestos products. Engine cylinder blocks were also commonly lagged in asbestos under timber or sheet metal cleading covers. Nowadays, the use of this once common product is prohibited, and today there is a thriving and profitable asbestos removal industry.

Most of John Oxley’s original asbestos pipe lagging was removed many years ago when the project was commencing. The decision was made at this time to encapsulate the asbestos underneath the main engine cleading. This was done and tests revealed that no remaining airborne asbestos dust contamination.

In 2012 we revisited this decision following concerns that accidental damage and corrosion might release hazardous asbestos particles. What followed was a program to remove this asbestos. Quotes were requested and the least expensive option chosen.

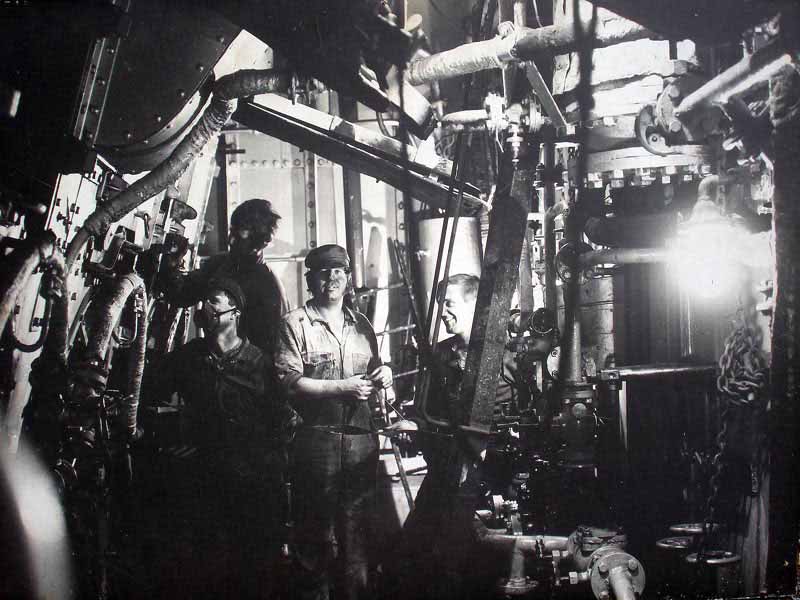

As the cylinders are some distance above the engine room treadplates, extensive scaffolding on both sides of the main engine was required so that the asbestos removal contractor could work safely.

Scaffolding was installed by sponsors Scaffold Training Australia and was left in place as a platform for our fabricators to use when needle gunning the deck beams and replacing the main deck.

Asbestos removal is a necessarily painstaking process. SHF people initially had to thoroughly clean the space concerned. From this point on only the contractors workers were allowed in this part of the ship.

Contractors employed on asbestos removal must be trained so that they do nothing to contaminate themselves, others or the environment. They work in sealed sheet plastic tents with ‘air locks’ and wear disposable coveralls and breathing masks. All asbestos removed along with workers coveralls and contaminated equipment is securely bagged and labelled before dumping as hazardous waste.

Final task is for an independent air quality hygienist to test the air in the engine room for zero asbestos contamination prior to our workforce entering the engine room again.

Fortunately it was possible to retain the original Russian Iron cleading sheets as the asbestos insulation was not adherent. Some of this cleading retains the original gun blue colour, but much has surface rust and has been already painted over. Being able to retain the original cleading will retain original fabric from the engine builders, plus it will save the work of replication.

With the asbestos and cleading removed, it is possible to descale the cast iron cylinders and apply rust preventative paint. It is likely that these surfaces have never been exposed since originally covered up by the engine builders some 86 years ago.

The accompanying image records the markings and labels originally painted in whitewash by the original Bow McLachlan fitters.

We must also thank an anonymous sponsor who generously sponsored this task.

Main deck aft and above the engine room

Under the John Oxley’s Teak working deck is her actual structural steel plate deck. While a ship’s deck is necessary for keeping the water out, decks must also carry large structural loads when a ship flexes in a seaway. They must therefore be in good condition.

Unfortunately, the steel plates under wooden decks are usually badly rusted. John Oxley is no exception. The hull team have started repairs aft and are moving forward, lifting the old wooden decking and then attending to rusted coamings and the steel decking beneath.

Progress so far has seen new steel plates laid and riveted over the engine spaces and work on riveting the steel deck over the pilot’s accommodation.

This is strenuous work and we are always seeking additional volunteers to help out here.

Following painting out of the upper engine room, the scaffolding can be removed and the engineers given back access to the machinery spaces.

Needlegunning and descaling

A constant in ship restoration is thick layers of paint and underlying rust. Chipping, needle gunning and wire brushing are usually the best way to remove these layers. On any day there are always part of the project where descaling and removal of old paint and rust is needed.

The project needs volunteers who are prepared to undertake this work. Their noisy and dusty contribution to the project is greatly appreciated. As well, there is great satisfaction to be gained from application of paint following the elbow grease and hard work.

Needle gunning also is a necessary part of Sea Heritage Dock maintenance. Image below shown Ian needle gunning some deck rust prior to a coat of Metalfix rust preventative paint.

Needle gunning is also a necessary part of Sea Heritage Dock maintenance. Image below shows Ian needle gunning some deck rust prior to a coat of Metalfix rust preventative paint. Image Ian needle gunning rust on deck of Sea Heritage Dock.

Fabrication – Bridge deck steelwork

Viewed from underneath, the steel structure of the bridge deck was clearly badly rusted. Some angles were badly deteriorated and some sections had rusted away completely.

The deckhead over the Master’s cabin had also been extensively repaired, which is in itself part of the history of John Oxley. It was clear that steel deckhead panels had been welded in under the timber wheelhouse deck and the fastenings that held down the steering engine had also been welded. We believe that the Masters of John Oxley were not happy with oil and condensate from the steam steering engine dripping on them through the deck, hence the welded inserts.

Interesting pieces of history that needed to be retained were the engraved beams in Master’s cabin and chartroom that indicated the use for that compartment plus the gross tonnage of that space. It is a common misconception to treat gross tonnage as a weight, when in fact it is a volume measurement that dates back to the age of sail.

It is a lot of work, but these engraved beams must be built back into the replacement structure.

The bridge deck is a complex structure. Parts are supported by the steel bulkhead aft of the Master’s cabin, while bridge deck beams are supported by the timber sides of the chartroom and Master’s cabin. The bridge wings were originally supported by steel rods; however. We believe the bridge deck was modified soon after arrival in Brisbane by adding steel reinforcing structure. We think that the forces from the steering chains showed up weaknesses in the existing structure.

Original drawings show the steel bridge deck plates only 0.20” or about 5 mm. thick. We suspect this is because the bridge deck is high above the vessel’s vertical centre of gravity and thicker plates might be too heavy to satisfy the naval architect.

Conversely, they sited the heavy steering engine in the wheelhouse. This was a common steering engine location for earlier vessels, but the crew on a Queensland based vessel would not have enjoyed a steering engine steaming up the wheelhouse.

The considerable weight of the steering engine is supported by the steel bulkhead behind the Master’s cabin and the timberwork sides of this cabin. The bulkhead also has cantilever brackets, which are warping under the load. They will need to be replaced and reinforced to better support the steering engine.

The initial task was to remove the wheelhouse. It took a lot of work to first find and release the fastenings that secured the wheelhouse to the steel bridge deck. With these removed, the wheelhouse was craned off and lowered to the deck of the Sea Heritage Dock where it is currently undergoing restoration.

Next task was to drill and cut out the rivets that secured the bridge deck to the structures beneath.

The steel plate bridge deck could then be removed by crane and brought down to the wharf. This deck was badly rusted and photos show how bad the deterioration was. A total replacement was required.

Barry and the fabrication team is now well into replication of this structure. A purpose built frame was erected to support the new steel angles. New steel deck plates are also being riveted in place onto this frame.

When these new decks are completed, they will be grit blasted and painted before being craned back into place and connected back into the ship’s structure.

Wheelhouse, chartroom and master’s cabin

As mentioned before, the wheelhouse has been removed from the bridge deck and placed on the Sea Heritage Dock for repairs. This is structure wholly built in teak but with steel fastenings in places. As these fastenings rust, they expand to form what is called a “rust bust”. These cannot be extracted as easily as they were driven in, so the team must chisel them out and repair the timber afterwards. The monkey bridge has also be dismantled and stanchions and railings placed in storage.

We knew that the timberwork in chartroom and masters cabin was also deteriorated and would need considerable restoration.

Steering engine

With the engine room ‘Out of Bounds’ due to asbestos removal work, the engineers have been busy ashore dismantling, cleaning and overhauling the Bow McLachlan steering engine. The John Oxley’s builders were making steering engines before they were shipbuilders and were a supplier of steering engines to all manner of naval and mercantile vessels. The steering engine fitted to John Oxley is a fine example of this type of engine and has been much admired by the John Oxley team and by visitors.

When removed, the engine could still run and was oiled up and tested on compressed air.

Dismantling could then commence and the engine was stripped down to the last nut and bolt. Fortunately most of the issues were cosmetic and the engine has now been largely reassembled and will soon be test run. It will be returned to the vessel when the bridge deck is returned.

Oral history from Queensland revealed that Masters when trying to snatch some sleep ordered the steering engine overhead of the Master’s cabin be shut off and the vessel steered by hand using the large hand wheel provided.

Fuel study, or what will a restored John Oxley burn in her boilers

(Held over from first half of 2013)

Since the 1970’s there has been debate on which fuel a restored John Oxley will burn. This ship, like so many others, was built as a coal burner. This was in a time when coal was cheap, thick smoke from funnels was expected and firemen could be readily found in union offices and waterfront hotels.

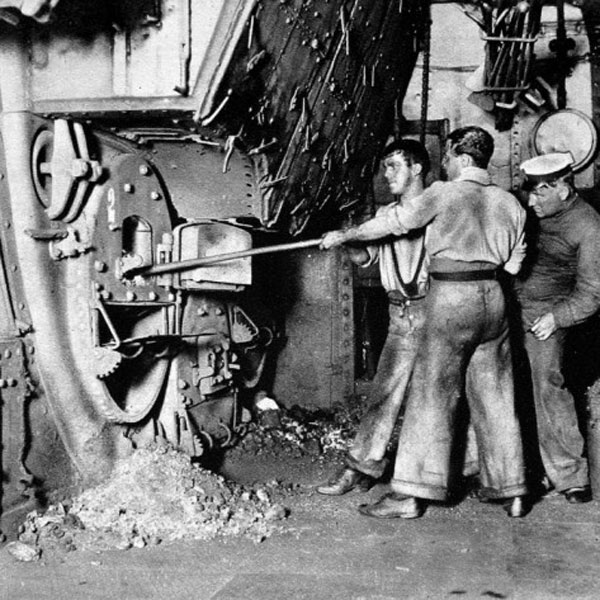

This image shows a very similar coal stokehold to John Oxley’s, except that on John Oxley, only one fireman worked each watch.

In 1946 and following complaints from firemen, the boilers were converted to burn heavy fuel oil or Bunker C, and John Oxley steamed on until 1973 as an oil burner.

Conversion of ships from coal to fuel oil was common in those days because Bunker C was cheap and the conversion reduced the number for firemen or stokers that were needed. Trimmers, who wheelbarrowed coal from the bunkers to the stokehold were also no longer needed.

In the 1980’s, SHF management decided the fuel for John Oxley was to be coal. Later studies reversed this decision and oil fuel became the preferred option. These decisions are periodically evaluated and in 2013, a much deeper and more detailed study was undertaken.

Dialogue with SHF and local steam locomotive operators all confirm that today’s coal is ‘run of the mine’ and is no longer screened and washed as it is intended for crushing and burning as a dust in modern boilers. This means that “3-4 inch cobbles screened and washed” is a thing of the past. Modern coal supplies have much smaller lumps and more fines. There are also higher levels of contaminants such as ash, stone and dirt. The old cheap heavy fuel oils have also been replaced by lighter fuel oils and by recycled oils.

While coal is initially a cheaper fuel, it is much more labour intensive to handle plus more coal is burned to achieve the same result. Another problem is the handling and disposal of large amounts of ash. Complaints from the public about coal smoke would be an expected problem.

Roads and Maritime Services surveyors were consulted and expressed concerns that SHF firemen would be less likely to have the physical endurance of the experienced coal firemen from earlier times. The ability of our ship to keep steam plus the physical wellbeing of our volunteer firemen in a stokehold with 6 large furnaces were major concerns in this study.

The 2013 study confirmed oil fuel as the preferred fuel for a restored John Oxley. It was acknowledged that oil fuel setup might be more expensive than provisions for coal and that additional WHS risks with oil fuel would need to be controlled. It is also possible that in the future a low Sulphur fuel will be mandated.

PROJECT BENEFITS

Preserving our nation’s maritime heritage

The basic purpose – value to the community through conserving maritime treasures and keeping alive the skills needed to restore, operate and maintain our maritime heritage.

Volunteering

The project provides an opportunity for people to learn new skills and to use existing ones. It is also an opportunity for social contact plus the forming of friendships between people on the same wavelength. The project is enjoyable to attend without the commercial pressure of people’s normal work environment. The volunteer workforce is physically active and mentally on the go. It’s not just for the men, as we also have many ladies volunteering on this project.

Our work at the moment needs more volunteers with welding and fabrication skills and those who can paint.

We are also seeking volunteers who wish to learn new skills and become part of our team.

Youth training

Our previous apprentices have been sponsored, and we would like to expand this valuable part of the project. Do we have anyone wishing to help here? We ask the metal industry the opportunity to sponsor further apprentices to work on metal fabrication.

Our apprentices have been vital to the restoration and there are now quite a few skilful tradies in the community who gained their qualifications from this project.

We have also had a number of apprentices loaned to the project by outside companies during light work periods. Another option is for apprentices to learn heritage trade skills if they volunteer on days off.

Economical use of funds and material utilisation

All purchases are well thought-out and nothing is wasted when materials are used. Even remnants of steel plate are used to make pipe flanges and for training welders.

EQUIPMENT SOUGHT

Most SHF tooling and equipment is donated by industry because it was commercially out of date or a workshop was closing. This works well for us as C1927 ships do not need high tech equipment. Generally, our donated machines feel quite at home.

The work team wish list includes:

Plain drill press – #3 Morse taper Horizontal borer – not too large! We are always needing to re-bore engine cylinders Drills and bridge reamers for 5/8″, 3/4″ and 1″ rivet work Nuts and bolts – all sizes – especially inch sizes Air hoses – about 25 mm for mains and smaller sizes for air tools

Seeking electric pumps

The pumps are needed sooner rather than later as we are fabricating the piping systems. These pumps are in addition to the steam pumps fitted to John Oxley.

|

75 mm. self-priming pumps for bilge service – 2 needed 75/65 mm. centrifugal pumps for fire service

75/65 mm. diesel fire pump

32 mm centrifugal pump deck wash

|

Can you help?

To visit the project or help with materials or services, please contact our office on (02) 9298 3888 or drop in on the project and ask to see Tim Drinkwater or one of the John Oxley team members.