Why Restore John Oxley

.

The restoration of the 1927 Australian steamship John Oxley to full operational condition is a major project being undertaken by Sydney Heritage Fleet. It is intended to preserve this historic vessel for future generations of Australians as the only operating example of the most common and significant form of early 20th century coastal travel.

This type of vessel was once very common in Australia and local waters. Ships of this type were the only way of moving cargo and passengers up and down the coast before rail and road transport links existed. These ships also serviced many Australian ports and as well worked up into the Pacific Ocean islands

Coastal steamships and travel has been largely forgotten. This project will bring back to life one of these vessels and recreate that experience.

Her cultural significance stems from the fact that she is the last steam engined coastal steamship left in Australian waters today. While some local and overseas ferries, steam tugs, colliers and a sludge carrier remain, there are no coastal passenger/cargo steamships of her size remaining intact today.

John Oxley represents a period in shipping where crews were rigidly separated by status. Deck crew and firemen bunked forward in the forecastle. Officers’ cabins were miships on the main deck. Pilot’s cabins were aft and below the main deck. The Master’s cabin was on the boat deck and just below the wheelhouse.

The crew worked long hours under conditions that were unacceptable to their unions, causing a number of industrial disputes as early as the late 1940’s.

.

Historic significance of John Oxley and its place in Australia’s maritime history

.

It may be asked how a Scottish built steamship, ordered for and operated throughout its active career by the Queensland State Government, is of international and national historic significance.

The answer lies in an understanding of the nature of shipping in the early 20th century, Australia’s early maritime history, the significance of John Oxley to that history, and the broader focus of SHF activity.

International significance

John Oxley is Clyde built, meaning it was constructed in that part of Scotland that was then world-famous for quality and technology plus the sheer numbers of ships built. As such, she represents the tradition of shipbuilding with its roots in the Clyde and nearby tributaries.

John Oxley has riveted hull, teak decks, two Scotch boilers and a triple expansion main engine – This arrangement is absolutely typical of this class of ship, and John Oxley is one of the few remaining coastal steamships remaining. Thousands of similar ships were built, and like the sailing ships before her, most have been scrapped.

National significance

John Oxley is the last remaining example of the large numbers of similar ships that once steamed around the Australian coast. As such, John Oxley is a priceless asset of extraordinary significance to Australia’s maritime heritage estate.

As in many areas of technological innovation, Australia was at the forefront of the use of steam for marine use.

Hundreds of steamships entered service between Australia and overseas and around the Australian coast. These vessels provided a regular and reliable service around our coastline, often faster and far more comfortable than early rail services.

Australians were more likely to travel and move their produce and wares from port to port by steamship, especially as the geographical reach of road and rail networks in the early 1900s was very limited.

There were also many coastal inlets and rivers – These were a barrier to road and rail transport, but these did provide many local and regional ports for ships to berth and load and unload passengers and cargo.

The high point in terms of size and luxury was the decade before the Great War from 1914-1918. Steamships of up to 10,000 gross tons – some as big as many overseas mail liners – plied Australian coastal waters carrying passengers and cargo. Many hundreds were smaller and more unassuming – some were only a few hundred gross tons and carried only modest amounts of cargo and handfuls of passengers.

Between the wars, steamships continued to play a major role in Australia’s transport infrastructure. Coastal travel declined quickly after the Second World War as road and rail networks were expanded.

John Oxley is highly significant as the only remaining classic example of the smaller type of coastal steamship. She is the last living example in this country of a most significant part of our maritime social history.

John Oxley’s work also enabled pilotage work along the Queensland coast and in and out of Brisbane. This was essential for the safe navigation of ships that carried passengers and cargo to and from Australia. John Oxley also serviced navigation markers, buoys and lighthouses, which is essential work for safe navigation even in today’s world.

Social signifiance

John Oxley’s crew arrangements date from the early 1900s when the lives of seafarers were considerably different from what is seen today.

Pilots when carried lived aft in comfortable cabins and they enjoyed steward service. There was one pilots’ bathroom with bath and shower. A pilots’ mess was available for pilots to enjoy meals and off-duty hours.

Officers berthed amidships in single cabins and also enjoyed steward service. The workload was hard as Master plus Mate, and Chief Engineer and Second Engineer had to handle 24 hour operation. During pilot transfers, the Master remained on the bridge while the mate skippered the whaler. During maneuvering, both engineers would be on duty in the engine room. As well, no greasers were carried so engineers “slung their own fat” (oiled around). Crew called this the “24 hours on system”. Officers and crew slept when they could.

The deck crew consisted of a bosun, a leading hand and 3 able-bodied sailors. No ordinary seamen were carried as pilot boat work required considerable skill and ability. Sailors normally worked the usual 4 hours on, 8 hours off system, however, it was “all hands” during berthing and during pilot transfer work. Rest and sleep would often be an afterthought. Deck crew berthed in the starboard side of the forecastle. The crew slept or rested when they were off-watch. One of the crew was nominated as the “peggy”, whose duties involved carrying meals forward from galley to forecastle. Another deckhand ran a canteen that sold tobacco, soap, razor blades and other goods needed by the crew.

3 firemen were carried – They stoked fires and deashed. 3 watches were normal and again on the 4 on, 8 off system. This meant that only one fireman was allocated for each watch and was required to fire and deash 6 furnaces. For longer trips a trimmer was carried to shift coal from bunkers to stokehold.

John Oxley also carried a cook and a steward. They berthed aft in a small cabin in the pilots’ accommodation.

Of special significance is a newspaper cutting taped to John Oxley’s crew mess bulkhead and found by the Brisbane to Sydney crew. It details an industrial dispute undertaken by the Seaman’s Union on behalf of the John Oxley crew who objected to long periods of work without rest and sleep during heavy pilotage frequencies. The Union lost this case.

John Oxley’s crew were mostly permanents, however, temps were needed when crewmembers were on leave or ashore for medical reasons. They usually lived in nearby Brisbane suburbs. Officers were often more mature aged, however, sailors had to be young and strong as required for regular boat work.

Technical significance

When built, John Oxley was just another coastal steamer, however, this vessel is seen today as being a very typical example of this once-common type of vessel.

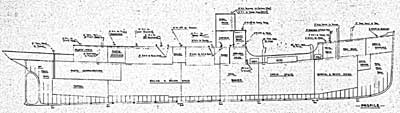

Construction is riveted steel hull plates on steel frames with teak decks. Machinery spaces also had a steel deck overhead. John Oxley has a well deck and main hold serviced by a mast and derrick. This derrick was first driven by the ship’s windlass, which may have been a cumbersome arrangement for a buoy handling vessel – A Clarke Chapman deck winch was a later install and took over this work.

A much higher aft mast was later installed in response to navigation light regulation changes.

John Oxley has a pilot mess and cabins aft – This copies vessels that had passenger accommodation aft and cargo spaces forward. Officers had single cabins amidships while the Master’s cabin was beneath the wheelhouse.

Crew were accommodated in the forecastle. John Oxley is the only remaining ship in Australia to have a traditional forecastle forward of the mast and above the main deck.

The wheelhouse is not large and would have been uncomfortably hot working along the Queensland coast. The chatroom is located beneath the wheelhouse and a monkey bridge is above. Monkey bridge has an Azimuth ring compass.

A galley is installed amidships along with the original coal fired galley stove and benches.

When built there were 2 clinker lifeboats and a jolly boat slung from davits on the boat deck. The 2 heavy lifeboats were replaced in Queensland by light weight clinker pulling boats more suited to pilot service.

The layout of John Oxley’s spaces and arrangements is very typical of coastal steamships from the early 1900s. Similar vessels had similar layouts even when diesel propulsion became more common.

Propulsion was absolutely typical with two scotch boilers and a triple expansion main engine.

Surface condensing was usual for the time and a Bolton Paul enclosed steam engine drove the circulating pump.

The propeller by Stones was a built-up type with a cast iron hub with bolted on Stones Metal blades. The stern tube was oil filled type with conventional packing forward and a patent seal aft. A Michell Bearings thrust block was fitted. John Oxley’s shafting passes through a bulkhead gland and a watertight door is installed here as well.

John Oxley’s main engine did not have lever-driven pumps and a Dawson and Downie shuttle valve lever-type air pump was installed. A dual Weir main feed pump set feeds the boilers and a Weir float tank controls the speed of these pumps (This was a Lloyds and BOT requirement where independent main feed pumps were installed).

Howdens forced draft with air heater was usual for the time. John Oxley was coal-fired from 1927 to 1946 when a conversion to heavy oil firing was carried out.

110 volt DC electric light was supplied by a Sisson enclosed steam engine driving a 7 kW Crompton generator set. A cool room with steel coils was fitted along with a Reader enclosed steam engine driving an L. Sterne Ammonia refrigeration set.

The fire and bilge pump was a vertical Dawson and Downie duplex pump. A larger Dawson and Downie ballast pump could also act as a backup circulator for the condenser. A Worthington Simpson horizontal steam fire and bilge pump were a later install by Queensland Harbours and Marine.

A Bow McLachlan steam steering engine was installed in the wheelhouse with chain and rods to the rudder quadrant. Bow McLachlan specialised in steam steering engines and supplied many liners and the Royal Navy.

John Oxley’s steam machinery plant is absolutely typical of steam plants from this time. It represents almost identical steam plants installed in coastal ships, steam tugs, steam ferries and naval support vessels from the 1920’s.